Yellowstone Wilderness in a Box

At the Crossroads of Art, Science, and Conservation in Yellowstone

Karen B. McWhorter

James Prosek is an artist, naturalist, and author. At rst glance, many of his paintings might remind viewers of carefully-rendered natural history illustrations. Their familiarity derives from Prosek’s use of an artistic vocabulary codi ed by artist-naturalists like Titian Ramsay Peale, John James Audubon, Edward Lear, and Thomas Moran. Looking to these artists and the eld guides they inspired, Prosek often isolates a particular animal or plant from its natural environment, depicting it in exacting detail against a monochromatic backdrop. As in American Bison (2014) (facing page), Prosek might ank a central creature—in this case a single buffalo—with a selective sampling of plant and animal specimens of a smaller scale, here three sprigs of Indian paintbrush and a black-billed magpie. These species’ juxtaposition suggests a relationship between them, and indeed, these three all are endemic to northwestern Wyoming. His choices of subjects and the way he orders them also calls into question the hierarchies and boundaries that we create in our minds between plants and animals, between species, between everything in nature.

Prosek’s frequent choice of watercolor, his preferred medium since childhood, is also reminiscent of earlier artist-naturalists. In this way, too, his work evokes associations between watercolor paintings and exploration. Artists historically used watercolors in the eld for practical and philosophical reasons. Watercolors are more portable and dry more quickly than oils and were, and continue to be, a popular medium for painting en plein air (out of doors). Watercolors can also suggest immediacy and intimacy with one’s subject. A personal, one-on-one experience with his subjects has long been an important part of Prosek’s process, which is fundamentally informed by close, attentive observations of nature. His desire to study his subjects in their natural habitats has taken him on journeys to remote and sometimes dangerous places across the globe and, for the Invisible Boundaries project, frequently to the Yellowstone backcountry.

Though Prosek’s choice of subject matter, his painting style, and his penchant for eld work may nod to earlier artist-naturalists, his intended message is more provocative than that of his predecessors. He uses traditional representational techniques but moves beyond documentation to tackle contemporary issues, creating works of art that are engaging and often subtly subversive. Thus, Prosek crafts stunningly beautiful works of art that offer lessons in environmental consciousness.

Prosek’s paintings of creatures paired with numbers, like American Bison (Wyoming) (2014) (see page 4), suggest that there exists somewhere a corresponding list the animals’ names, but this is not the case. He leaves us at loose ends; there’s no inventory of the creatures he portrays. Rather than resolve this conundrum for the viewer, Prosek encourages us to reject on the need to “know” and the imposition of tidy systems on a wonderfully messy world. This is a principal theme in Prosek’s work: an examination of our human propensity to name and order nature and, as he says, “our prejudices and priorities” in such attempts at control. His paintings often confront the limitations of language in describing Earth’s incredible range of biological diversity. Nature is dynamic and yet we expect that static names and categories can de ne it. We feel the need to organize it, to chop it up—though nature doesn’t lend itself to clear divisions, we force them nonetheless. Prosek is intrigued by the conceptual lines we draw between things, like the divisions we create when we ascribe classifications to plants and animals. He is concerned with how these manmade lines affect how we think about and act toward the world around us.

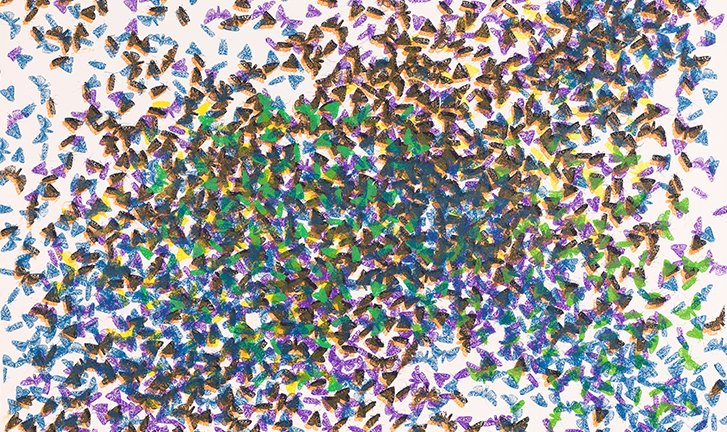

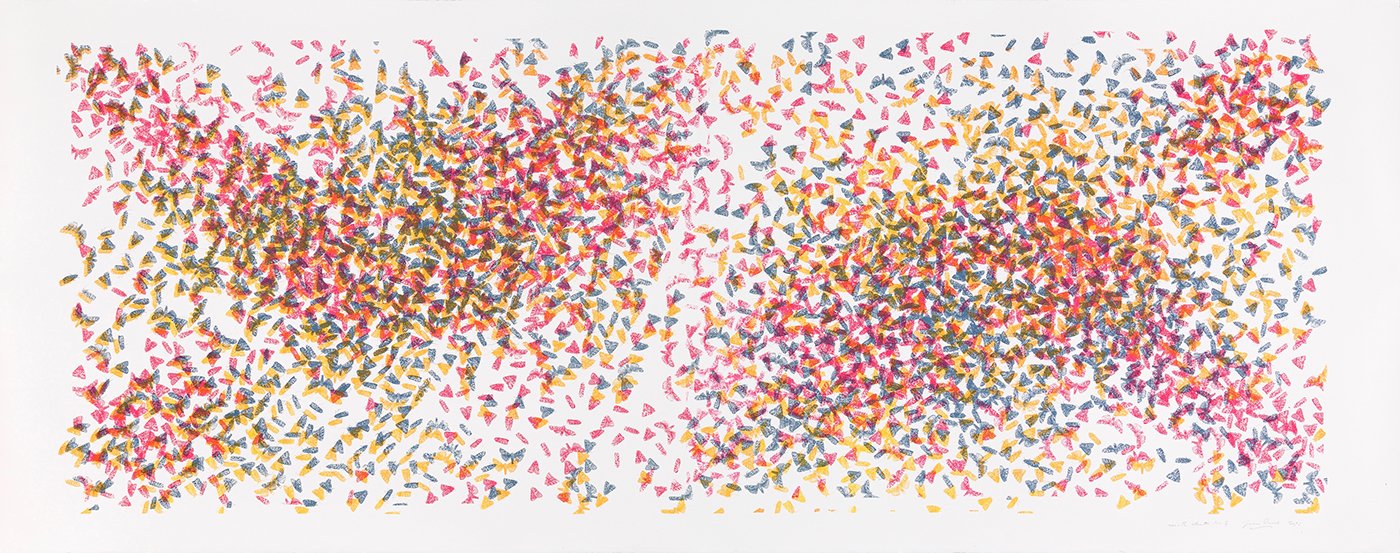

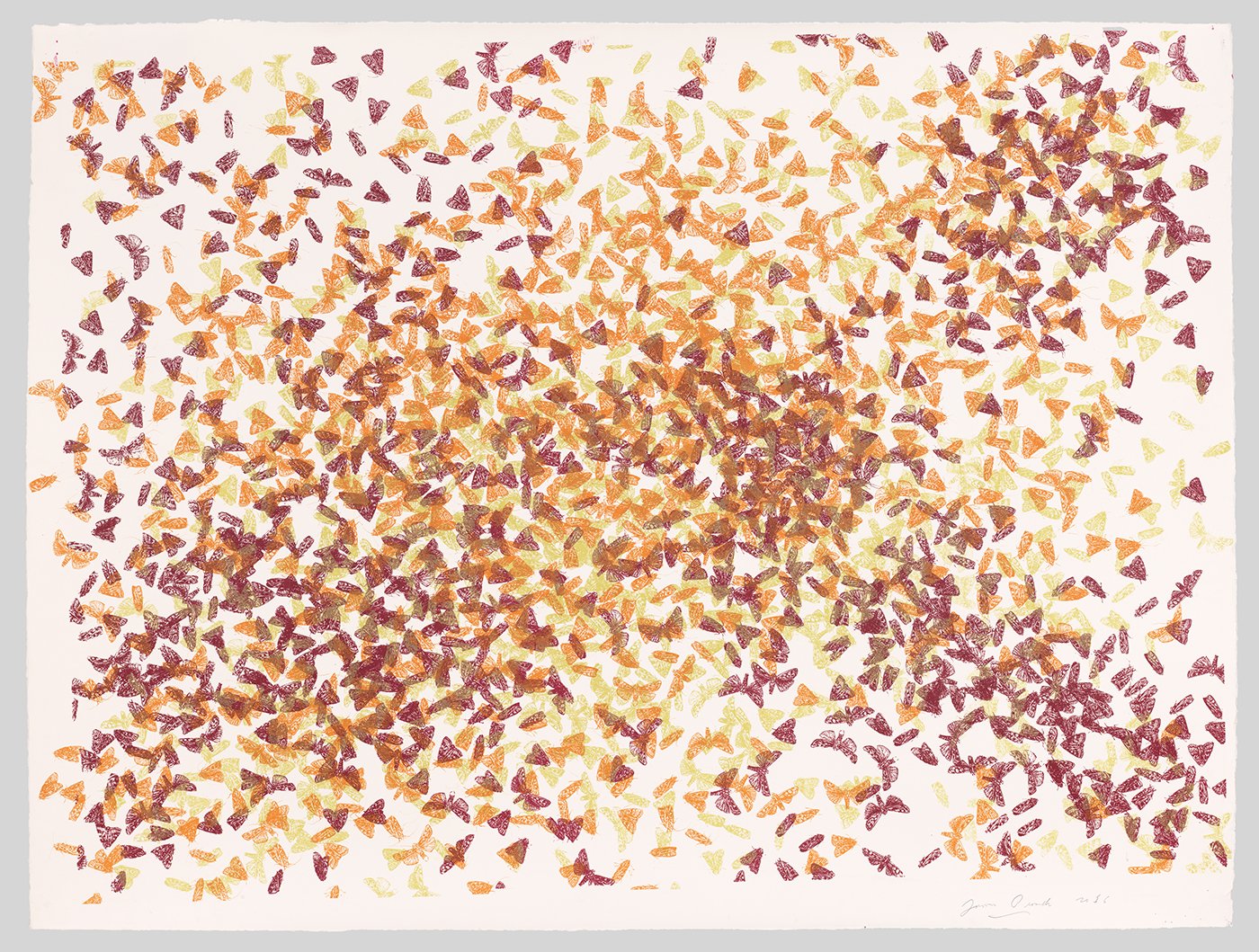

For the Invisible Boundaries project, the protagonists of Prosek’s paintings are regionally-specific species, with starring roles played by Yellowstone’s hooved herbivores including elk and bison, among the most familiar species of the region. Lesser-known actors in Prosek’s narratives include the western tanager, the rufous hummingbird, and the army cutworm moth, animals we might not readily identify with Yellowstone but which depend on the area as a stopover on their long-distance migrations. Prosek’s inclusion of these species points to the fact that Yellowstone’s reach extends farther than most of us realize. Prosek’s artwork encourages us to think about Yellowstone as an ecosystem that de es its borders.

Prosek’s paintings of animal silhouettes, like Yellowstone Composition No.1 (2016) (see page 6), speak to the interconnectedness of the natural world. These silhouette paintings might remind viewers of a puzzle in which the animals should t together in one pre-determined order, but don’t. According to the artist, We think that by just replacing a missing puzzle piece, like the wolf as apex predator, that the ecosystem will be “OK” again. That may be true to a certain extent but it’s certainly not the whole story. In some ways we have to simplify histories and biological interactions in order to tell a narrative, to communicate, but there is a lot of nuance left behind.

At the heart of Prosek’s paintings is the idea of connectivity: Yellowstone as linked to surrounding and far- ung environs; Yellowstone’s plant and animal life as dependent on each other and their human neighbors.

Yellowstone National Park’s nearly rectangular boundary was originally meant to encompass geological and scenic wonders. The region’s biological wonders—especially its unique animals— are more difficult to con ne. Some insects, birds, and mammals that call Yellowstone home for part of the year regularly migrate well beyond the park’s perimeter. Through his artwork, presented

in Yellowstone: Wilderness in a Box, Prosek suggests that trying to contain nature—within park boundaries or otherwise—denies the natural world’s hybridity and fluidity.

Excerpt/Adaptation from Invisible Boundaries: Exploring Yellowstone’s Great Animal Migrations (Cody: Buffalo Bill Center of the West, 2016)

January 20 – June 4, 2017

The Art of James Prosek

Buffalo Bill Center of the West

720 Sheridan Ave

Cody, Wyoming