Symmetry & Myth

Catalog Essay

James Prosek comes to art through his life-long love of nature—in particular, fish. As a child, he began painting in watercolor the native brook trout near the streams of his boyhood home in Easton, Connecticut. Later, research on the trout of North America culminated in the book Trout: An Illustrated History, which included seventy watercolors accompanying the text. So devoted was he to this passion that the book was published while Prosek was still an undergraduate at Yale. Dedicated to the notion that living things are best studied in their natural environments, Prosek traveled extensively. His last book on trout, Trout of the World, took him to the rivers and streams of the Mediterranean, Adriatic, Black, and Caspian Sea basins.

This recent body of work is a departure from the tradition of direct observational Audubon-inspired watercolor illustration. While elegant, his earlier illustrations do not investigate critical issues of the scientific endeavor that have always interested Prosek. Recognizing the subjectivity of scientific inquiry, our overweening ambition to collect and control nature through classification, and the fact that natural variation is perhaps even more fantastic than any fiction that artists might devise, Prosek presents us with an assortment of inter-species hybrids, part bird, part fish, part reptile. One creature—a highly evolved woodpecker—takes the idea of inter-species coupling a step further into the realm of science fiction. In this instance, Prosek concocts a cyborg-like entity, part animal and part machine. Prosek’s woodpecker has a drill bit for a beak and a Swiss Army knife for a tail. Here, he raises the question, could nature, through natural selection, adapt to mimic the tools of human industry in order to survive in a world increasingly dominated by human beings?

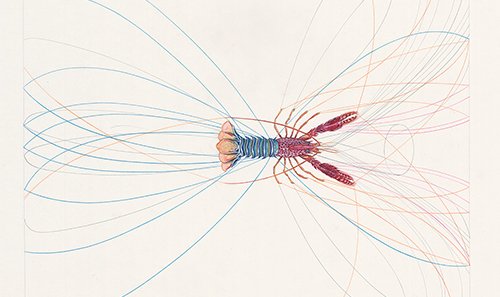

Prosek’s hybrids stem from the recognition that categorizing the natural world is an attempt to describe the ineffable, that as soon as we begin classifying, we tend to subvert our best intentions. Riffing off of our linguistic folly at naming nature, Prosek paints animals that seem wholly plausible, but are his own creations. His kingfisher is a fusion of a kingfisher bird and brook trout; a turtledove is a combination passenger pigeon and box turtle; a pegasus is a seahorse with the wings of a yellow-breasted chat.

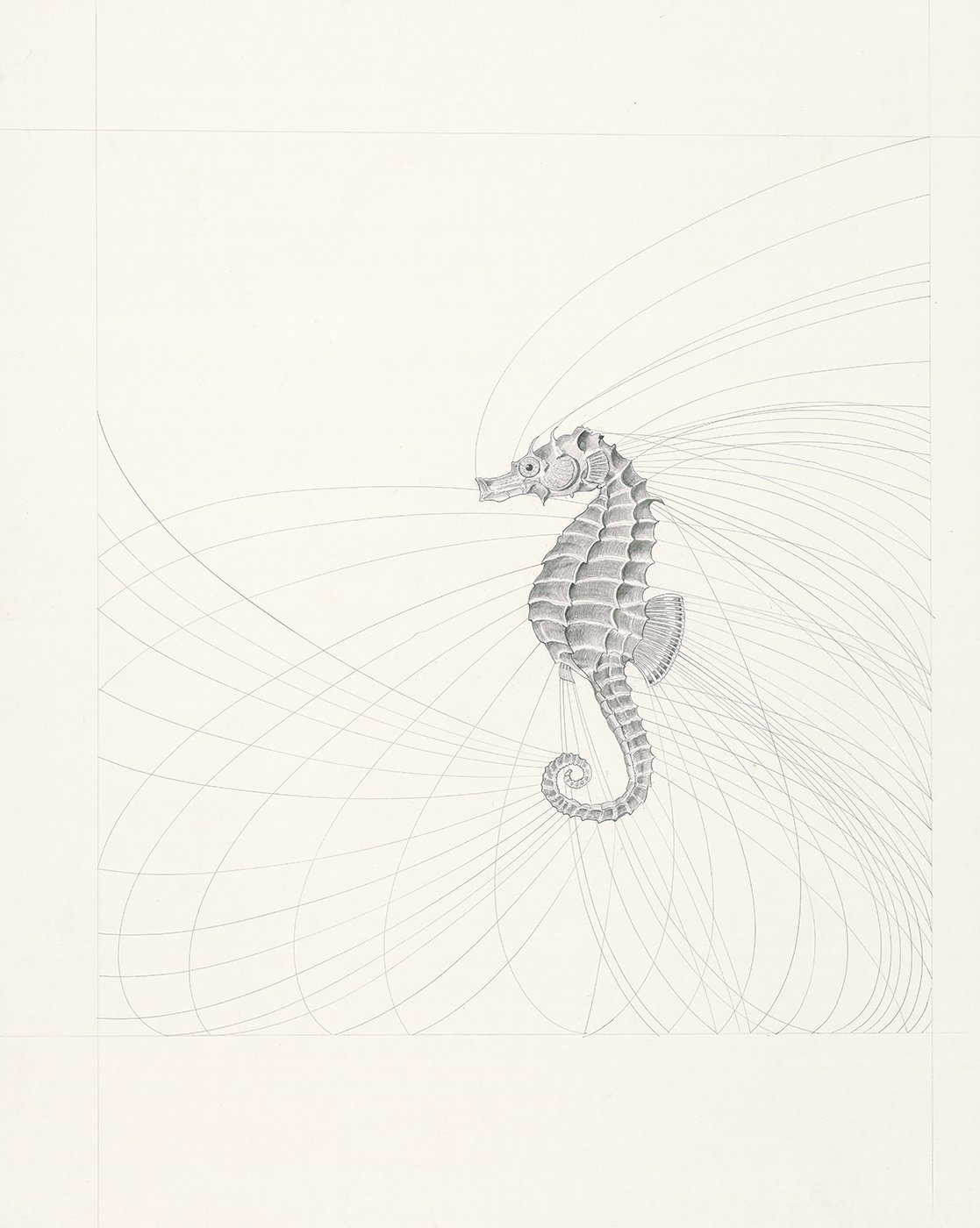

Prosek has also painted an image of a seahorse in juxtaposition with an outline of a part of the brain called the hippocampus, which is the scientific name for the seahorse. When viewed in cross-section, the end of the hippocampus curls up like the tail of its namesake. Before the advent of scientific classification, hippocampus described mythological underwater horses, perhaps similar to mermaids. Scientists later decided to keep the mythological name. This image relates to Prosek’s desire to underscore the deep connections between science and myth, which may be perceived at first glance as mutually exclusive conceptual frameworks, but are simply two different perspectives employed to make sense of the world around us.

In the context of contemporary art, Prosek shares kinship with artists who look to the tradition of natural history illustration (Walton Ford), the creation of hybrid creatures that seamlessly dovetail into the realm of the authentic (Thomas Grunfeld), as well those who re-invent traditional modes of expression for new purposes (Shazia Sikander). Walton Ford is known for his meticulously rendered, classic images of birds and other animals that at first appear similar in style and technique to artists such as John James Audubon and Alexander Wilson, but on further inspection, prove to be commentaries on a wide variety of political and ecological concerns. Thomas Grunfeld creates misfit taxidermy sculptures in which he combines two unrelated animals creating fictitious hybrid species that resemble bizarre experiments in genetic engineering. Finally, Shazia Sikander retains the materials, techniques, styles, and even some of the characters of traditional Asian miniature painting, but subverts the genre with a feminist perspective and the depiction of contemporary concerns.

It is interesting that a cataloguer of natural history would revert to a fantastical aestheticization of animals. But Prosek was never trained as a scientist and understands the subjective aspects of scientific classification. Furthermore, as his exploration of the seahorse/hippocampus suggests, there is a long tradition of fantasy projected on to nature in the name of science (and myth). From the age of exploration to the present, natural historians have invented odd species in accordance with their desires for the exotic other—animal and human, grotesque and beautiful. Prosek’s recent art gets to a core issue of how we see the world around us, natural or otherwise—we see things through our own idiosyncratic, flawed human lenses and there is no denying this.

May 3-June 3, 2005

Fleisher Ollman Gallery, Philadelphia

by Alex Baker, Curator of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia Academy of Art